Ian Hamilton Finlay, Poster Poem. Image: Iliazd, flickr.com/migueloks

To the Poetry Library, then, for a tour and introduction to the history of concrete poetry in anticipation of Poor. Old. Tired. Horse., courtesy of Poetry Librarian Chris McCabe. The Poetry Library houses the Arts Council’s modern poetry collection, its definition of ‘modern’ being post-1911, and it pursues comprehensiveness in collecting the entire poetic output of the UK, including ephemeral magazines and self-published chapbooks, as well as a representative sample of international poetry publishing.

It’s a brilliant place: its collection is available in stacks in the library on the fifth floor of the Royal Festival Hall; you can just drop in and consult a text. It’s also digitising its poetry magazine collections and putting them online. I first discovered the library in the mid-1990s, and rather arrogantly dropped off two copies of my own chapbook, one for reference and one for lending, both of which I’m always gratified to see they still have.

McCabe introduces the place, and shows us the library’s current exhibition, Lucy Harrison‘s Poetry Machines, a work that takes scans of individual words of poems and cycles them across a row of video screens to produce an multiplicity of new poems in the manner of Raymond Queneau’s seminal Oulipo work Cent Mille Milliards de poèmes. But the real treat is that upstairs, along the entire length of the St Paul’s Roof Pavilion, laid out for us along thirty or so feet of tables is the history of concrete poetry using material from the archive.

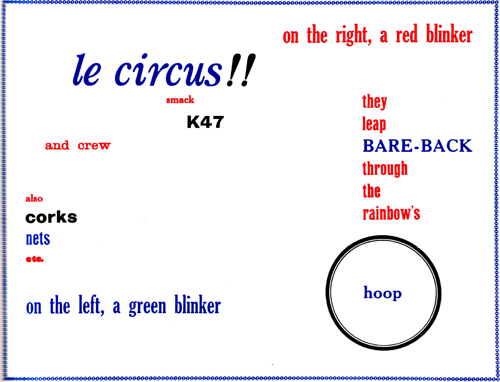

It begins with Lewis Carroll’s Mouse’s Tale, progressing through magazines of 1960s avant-gardeism like Second Aeon, and the curious letterheaded subscription mailings of Private Tutor. There’s a whole table devoted to the gorgeous works of Ian Hamilton Finlay, mostly in the form of fragile little pamphlets featuring boats, and also postcards (of boats) and a card of a lovely-looking neon work. A lot of Brazilian stuff (the combination of typeface, round vowels and Portuguese nasal intonations seem to all go strangely together). Oddities include Colin Sackett’s Black Bob, in which a single frame of the Dandy comic strip is repeated across 63 identical spreads and a curiously sealed package including the work of Tuli Kupferberg backed with a correspondence about the intellectual property rights in the name ‘Poetry’.

Hamilton’s son, artist and poet Alec Finlay is there too, and of course the library’s own collection of Poor. Old. Tired. Horse. itself, missing a few copies and containing some stunning work by Mary Ellen Solt, John Furnival, IHF, Bridget Riley and many others. The explosion of inspiration in concrete poetry is evident in the sequence of the magazine itself. It starts out as a simply folded poetry magazine with illustrations and evolves into something else entirely, with entire issues devoted to a single collaboration between a poet and a typographer. My favourite might be Ronald Johnson and John Furnival’s Io and the ox-eye daisy, in which letters morph and move through each other in a brown-blue moonscape.

On further tables there’s a beautifully colourful shape-of-the-sun poster by Dom Sylvester Houédard, and Furnival’s extraordinary lithographic renderings of the Eiffel Tower and the Leaning Tower of Pisa, densely packed with an inky allusive vocabulary. More recent works include Sam Winston’s Dictionary and a fabulous set of large fairytale-based prints, and Rick Myers’ limited edition boxes of texts and objects.

It’s properly impressive, and we all feel rather flattered that McCabe has taken the effort not only to get the stuff out of the archive, but also to construct an approachable intellectual history of concrete poetry. In some ways it speaks of its marginality; Finlay aside, there are few very well-known names here, and not many journals or publications dedicated exclusively to the form. You get the feeling that, like the villanelle or sestina, concrete poetry is now something that poets try their hand at as a demonstration of their virtuosity rather than a poetic tactic or affinity. In other ways, McCabe has drawn out an enduring tradition of the verse that pays attention to shape, and its ongoing exploitation of the tension between visual form and the internal ear. Either way, it feels like a privilege to be able to pick up and leaf through such an extensive display rather than gaze mutely at it through the glass of a vitrine. The more recent work that he has lad out for us, perhaps with an eye for our artistic sensibilities, comes in the form of limited editions, multiples and artists’ books like those produced by Coracle Press: poetry that has taken not so much visual inspiration from contemporary art as economic.

Walking backwards to the sixties tables, something strikes me about the confluence of poetry, art and radical politics. I’ve been looking at some old ICA bulletins recently, in particular the November/December 1967 issue that includes Tjebbe van Tijen‘s own photo-story of a continuous drawing from the ICA to Amsterdam, involving sarcastic humour and confrontation with the police at the bottom of the Duke of York’s steps, and John Sharkey’s ‘Popular Cut-Out Piece’. It seems to demonstrate a convergence of the radical, poetic and artistic in the ICA’s swish new premises on the Mall that’s unimaginable now.

Of course, in most ways, this radicalism was an illusion: Sirs Penrose and Read’s rather aristocratic ‘playground’ was then still an elite institution, and as such could tolerate the kind of disruption that posed no real threat to its audience’s place at the top of the pile. This kind of spectacular radicalism also worked as a kind of inoculation against real threats to the social order, a demonstration that British society could tolerate the counter-culture (whereas in reality, it couldn’t tolerate real change like equal wages for women or civil rights in Northern Ireland), an alibi for its continued reactionary existence.

Still, it’s hard not to feel some kind of nostalgia for the time when it was possible to discuss politics, poetry and art with the same set of people. Radical politics hangs on somewhere in the recent G20 protests, and if the theatre of protest still exists courtesy The Government of the Dead, there’s certainly little revolutionary fervour in the new East End, where ‘emergent artists‘ seem to be more interested in producing mediocre car advertising than changing the world. And poetry… well, some people are still reading poetry. Some people, like Daljit Nagra and McCabe himself are even writing good poetry. But compared to making art, writing poetry today seems a rather perverse and recondite activity.

Both contemporary art and contemporary poetry share a position realms of the ne plus ultra, in that anything goes: there are no limits to experimentation in form, elaborations of concept or nature of content. It’s a situation similar to the way that academic discourse can only be challenged through the medium of academic discourse itself. They’re the places in which the extreme end of our social dreaming can take place: while this often limits their relevance to our actual lives, contemporary art and poetry both have an essential role in exploring the limits of human creativity.

In status, however, they are completely unequal. While in recent years contemporary art has more than ever basked in the luxury of international money and media attention, epitomised in the Frieze Art Fair, an event which each year has me reaching for the Taliban application form, even among the literati poetry seems to be fighting a losing battle against prose fiction. While the Poet Laureate and the most recent winner of the Turner Prize seems to attract an equal measure of controversy and derision, Andrew Motion scarcely feels like a fair match for Mark Leckey. McCabe himself might be more like it, but there’s no competition for emerging poets that seizes the public attention in the way that even Beck’s Futures did for art.

In the end it seems hard to put this discrepancy down to anything other than our old enemy, the commodity. While both poetry and art share a similar social function, art can be bought and sold: it has literal value, and value attracts attention and social activity. That the power of the market has then affected the amount of attention that we pay to each form, and the access we have to each is unsurprising. The relationship has been distorted to the extent that capitalism itself is a distortion of life. Shelley’s ‘unacknowledged legislators‘ remain unacknowledged.

If poetry has derived any benefit from its non-object, reproducible status, perhaps it’s this: the Arts Council’s own collection of contemporary art, constrained by budget, foresight and all the other vicissitudes that make art buying a popular hobby of investment bankers, is actually a rather poor affair. By contrast, the collection of poetry belonging to the Arts Council that lives in the Royal Festival Hall is, as we have discovered through looking at only a tiny fraction of it today, an invaluable archive and an exciting resource. After McCabe has concluded our tour, I shyly-proud pull my own volume off the shelves to show my colleagues, hopeful that they’ll be impressed and petrified that they might actually read any of it: it’s a pretty appalling piece of juvenilia. But that’s the beauty of this place, and of poetry: looking after things, however little they apparently may be worth.