Trainee trapeze artists on Pier 40

Jesse McDonough is a man who loves New York in a way that I’ve only ever seen people love London. Studying American History in Maryland, where colonial-era studies rule, he chanced on a professor whose speciality was New York and the bug stuck. Cycling being his other passion, his final project considered how bicycles literally paved the way for the coming of the automobile to America. Now he runs Bike The Big Apple, leading tourist posses on pushbikes round the city, cycling along streets that are normally intimidating enough just to cross. His outrider Wendy brings up the rear, sitting in front of SUVs and issuing admonishments to their drivers: as hardcore an urban cyclist on a fixed-wheel bike as you’d ever hope to meet.

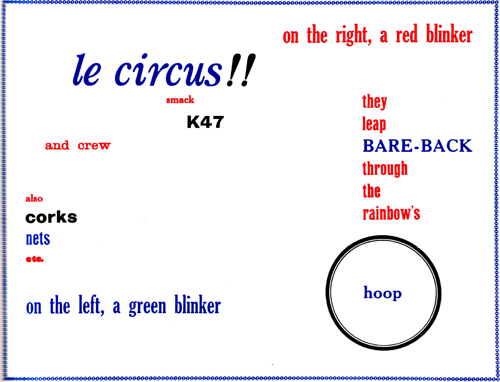

Cycling across Manhattan and through the West Village, we see where some of the richest homes in Manhattan have been (the focal point of desirability has moved steadily up Fifth Avenue throughout history, but always sticks to the spine, the street furthest from the filthy water’s edge), now greedily absorbed by NYU’s property acquisition programme; Christopher Square, with its monument to the Stonewall riots; and Manhattan’s thinnest house. We stop at Pier 40 and climb to the top to see a trapeze school (learners are held from falling by bungees) and football being played on the rooftops: Jesse says he plays in a league whose games sometimes kick off at one in the morning.

Rounding the southern tip of the island to catch the sun setting over New Jersey, we cycle through Battery Park City, a westward extension of the island built in the 1970s on the rubble excavated from the site of the World Trade Centre when it was built (there’s still no sign of a replacement). New York’s ability to hold tight skyscrapers comes from its bedrock, Manhattan schist: they rise highest downtown and in midtown because this is where the rock is firmest and closest to the surface.

We cross the Brooklyn Bridge (a good boardwalk, but a squeeze when only a quarter of it is yours: half the cycle lane going one way). The Manhattan Bridge back is better: barely a soul walking and gorgeous views back over the Brooklyn Bridge and downtown Manhattan, flying fifty feet over the Lower East Side. On a small stretch of street where an apartment block now stands, Jesse stops and shows us the place where his great-great-grandfather, an Italian immigrant, opened a barber shop. This is how it isn’t for Londoners, whose passport is their Oyster card: returning to New York is coming home.

*

Along 125th Street, in murals and on badges and posters, the parade of heroes: Malcolm X, Michael Jackson, Barack Obama. Revolutionary, tragedy, politician: all, somehow, part of the same story.

*

At the Nuyorican Poets Café on 3rd and B, they signal their appreciation of a poem mid-flow with finger clicks, elegant and insect-like micro-applause. Host Jive Poetic, a Brooklyn schoolteacher, does the borough shout-outs; if you’re from out of town, he advises, say you’re from Queens. It’s a proper slam: three judges from the audience hold up Olympic-style score cards at the end of each poem and get cheered and booed in equal measure if the rest of the audience disagree. The styles are more varied than you might expect: stand-outs include the softly urgent ‘Ode to my junk’, a paean to the variety of vaginal pleasure; and an anti-evangelical rant by a poet left sitting at the roadside after a crash by a man wearing a ‘What would Jesus Do’ bracelet. There’s a dominant mode of verse, though: strongly rhythmic, laden with rhymes and assonance (only in this part of the world could you rhyme ‘think’ and ‘bank’); and subject matter revolves around personal identity, trauma, and social injustice. Fair dos: there are more poets here who’ve seen the inside of a prison cell than you’d get at an average reading above a pub in London, but all five finalists are men, all wearing streetwear (t-shirts over long sleeves, hoodies), all talking rhymes with a heavy hip-hop influence. The best for my money is Hasan Salaam, but there’s a good Christian poet whose name escapes me; his stuff circles round to refrains, and he removes his baseball cap and holds it in his hand as though to beg halfway through each poem. The night’s winner, Tre G. finishes with a horribly sentimental poem imploring a woman (‘baby girl’) not to have an abortion (her heart must be ‘cold as ice’), which leaves the evening’s end itself more than a little cold.

*

18 miles of books at the Strand. Books seen on prominent display in more than one place: The Coming Insurrection, Huey Newton’s Revolutionary Suicide, and The Works: Anatomy of a City. Closest match to the ICA bookshop: The New Museum bookshop.

*

The punters with the audio guides know which paintings are important: they cluster round them like flies on a favourite turd. At the MoMA, two floors of the History of Modern remain as absurd and tedious as ever: the galleries below remain dedicated to whatever comes after Modernism; the best of which might be the exhibition of art-punk artefacts in Looking at Music: Side 2, though there’s something equally irritating about seeing the, you know, actual Marquee Moon cover (the same one you have at home) stuck to a wall, and watching the Rapture video on a big square gallery video box with headphones. These were artists who eschewed galleries, says the interp. That’s because album covers look stupid in an art gallery, and the same goes for Jonathan Monk’s collection of Smiths 12” covers.

The Whitney persists with a thematic hang of its collection, though far more minimally: the gallery invigilator laughs when he sees the little start I give as I notice I’m standing on a Carl Andre: he suggests I walk backwards along it. The Guggenheim hang is, of course, spiral: we learn that the best way to appreciate Kandinsky is to play word association games with the paintings, and that the later paintings have pleasing geometry. The Met surprises with a retrospective of Robert Frank’s The Americans, contextualised with social history and contact sheets from which the final selections were made (in a similar manner to the Barbican’s Capa show). Roxy Paine’s maelstrom of metal branches entangle the rooftop garden, and Argentino-brit Pablo Bronstein’s subtle pisstake in painstaking architects’ drawings of the neoclassical pomposity of the Met itself is quietly outstanding.

A lightning visit to the New Museum to see a retrospective of Black Panther Minister of Culture Emory Douglas’ art in posters and on paper. The Panthers’ combination of revolutionary attitude community politics is immanent in the work: women both carry guns and demanding the means to feed their families. One curious thing: for art that is first and foremost good and honest propaganda, the words of the slogans themselves are very small.

It would be a cliché to say that New York’s best art is on the streets; besides, subway cars remain resolutely silver these days. Nevertheless, Art in Odd Places, taking place this year from one end of 14th Street to the other is a far better game of hide-and-seek than spotting signature styles in an uptown gallery. Water-poems by fire hydrants, cut-up installations in shop windows, a campaign for Monty Burns for Mayor, and most beautiful of all, string crochet wrapped around razor wire protecting a vacant lot.

*

In Williamsburg, an earnest exposition of the roots of the current economic crisis is pasted on yellow paper to the wall. Across it someone has scrawled in pencil: Fuck Hipsters. The disease daydreams that it’s the cure.

*

In successive waves of immigration, each new ethnicity displaces its predecessor as they move out to better suburbs: this is the Lower East Side on the Tenement Museum’s Immigrant Soles walking tour, tracing paths through what was once a German neighbourhood replete with beer gardens, then Jewish, with shtiebels in houses until the Eldridge Street synagogue was built, now Chinese, with Buddhist house-temples much the same. ‘Little Italy’ is now merely a tourist island in Chinatown: profitable restaurants sitting under Chinese-owned, Chinese-occupied apartment blocks. When the Chinese move out, someone else will be here to replace them, says Nick, our ruddy-faced & enthusiastic ‘educator’ from Williamsburg.

This narrative of the endless racial recycling of the reserve army of labour is familiar from tours of London’s East End: the parade of immigration, the normalisation of new communities. It only falls apart a little when Nick points out a ventilation hose poking from a building window. An indicator of a sweatshop, he says; this particular ‘sweatshop’, which supplied stores in the city, was closed by the city after 9-11 when the neighbourhood was more-or-less shut down for a while. Pushed, he doesn’t seem to be able to say quite why; someone else on the tour explains that in fact this was a unionised garment factory (the kind of US-based labour force that American Apparel boasts about), and it closed because in the wake of the towers’ collapse, city stores outsourced the tailoring, and the factories never reopened.

It highlights something insidious about the story of foreign people redeemed through their immigration… when will rich countries run out of poor people to import as workers? What happens if they organise and refuse to accept their natural position at the bottom of the pile? Market-based arguments for multiculturalism are no arguments at all.

*

The Cyclone is closed for the winter and there are only two things left to do on a cold October day at Coney Island: eat a Nathan’s hotdog and shoot the freak. Five dollars for fifteen paintballs that splash harmlessly on the Freak’s shield, and a two dollar tip for the Freak’s college fund.

*

At the Hotel Chelsea, the central staircase used to look down on reception: they built a floor above it because residents used to throw bottles down. Residents still live there, leaving bikes in the hallways and taking dogs in the lift. But changes are afoot: mysteriously appearing on the streets around are flyers taped to lampposts and shop windows declaring that for the avoidance of confusion, Stanley Bard is no longer running the show. Someone has taped the word BARD large and then some other words in their first floor window. The front desk staff won’t be drawn on the situation.

Though David Combs’ famous painting of the Chelsea itself is under lock and key, the rest of the place drips with art: along corridors, in rooms, alongside every flight of stairs along the central stairwell. A sheet banner strung along a whole flight declares undying love for and devotion to the photographer Marcia Resnick. It’s hard to tell if she made it herself. The lobby is adorned with an erect dog. Heritage plaques on the outside say that this is the place where Dylan Thomas sailed out to die. Outside Sid and Nancy’s room there’s a picture of Nancy and a needle.

*

Tastes of the city: pancakes piled high in a lumberjack breakfast; cheese melted over a classic Reuben; fat, thick-rind bacon and grits at Sylvia’s soul food restaurant; a bowl of chilli at Katz’s deli; thin black coffee refills and ice water before you order; hand-pounded hot guacamole at Dos Caminos; nearly-liquid Kobe beef in delectable cubes at Joel Robuchon’s concession at the Four Seasons

*

A night at Jonas Mekas’ Anthology Film Archives with the short films of Pawel Wojtasik. They’re contemplative, with a touch of Brakhage-ish tension between the world represented and flat light falling on the screen. There’s something human about the porcine routine of Pigs: wake, squeal, piss, eat; but also something aestheticised in the rippling piggy hides, and the final money shot of a wall of pigs at war in the direction of a single trough is both hypnotic and repulsive. The Aquarium contrasts wild Alaskan waters with the Exxon-funded aquarium built in the wake of the Exxon Valdez spill: neurotic sea-creatures engaged in repetitive swimming routines. Nascentes Morimur is a film of an autopsy, from first incision to the removal of the brain. It approaches coyness with a digital apertures opening and closing on the work of the scalpel and saw through human flesh, hinting, but also taking something away. Afterwards, Pawel is in conversation; someone asks about filming the autopsy. He shot several autopsies, but used the first: the element of surprise and discovery was present for him as well for the audience. Even a dead person still looks like a person, he says, until they peel away the face.