Anti-art: Home and Childish

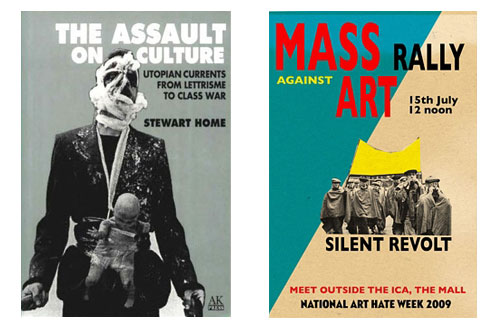

It’s best not to have literary or artistic heroes. Leaders will always betray you, and heroes will always let you down. As they slide into their dotage, as their work becomes weak and repetitive, someone will always taunt you with their latest fatuity, reminding you how much you once loved them (in my case a role usually played by my father). Their books and records on your shelves, their pictures on your walls, are like mementos of an ex you can’t bring yourself to chuck away. So, best not to have the heroes in the first place. Except: some people’s work grabs you, and you can’t let it go. In the mid-nineties, three people who fell into this category for me were Stewart Home, Billy Childish and Iain Sinclair. Not only for how or what what they wrote, but also because they wrote about an interweaving, overlapping knot of things that mattered to me: poetry, resurgent Londophilia, anti-art polemics, post-Trotskyist politics, popular culture and the Situationist International.

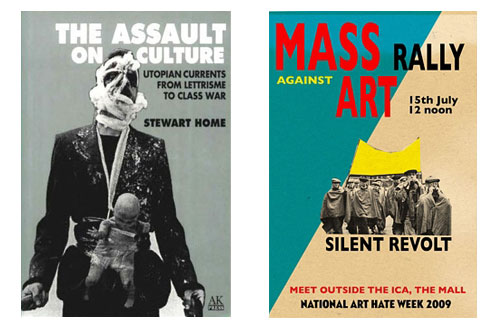

Both Childish and Home have a history of polemic against my old employer, the Institute of Contemporary Arts (worse than either heroes or leaders, places like that: if you make the mistake of forming an attachment they’ll rip your fucking heart out). Home imagines its violent destruction by the masses in Defiant Pose; Childish as recently as last year targeted the place as part of Art Hate Week. And now, in the space of two weeks, all three of them appear at the ICA, just when it’s going through one of its episodic convulsions (mass redundancies and a departed head of exhibitions; the chair of its council is said to be flinging papers across desks in fury and falling through chairs at meetings). It’s like… well, it’s like something out of an Iain Sinclair book. A storm of synchronicity. This can’t be missed.

At the Childish’s private view it’s good to see old colleagues and catch up on current horrors. The new Childish paintings are better than the ones I saw at L-13 a couple of years ago. Estuarine landscapes and defunct steamboats, portraits of Robert Walser’s snowy corpse, a character that Billy integrates his own self-image into, via Knut Hamsun’s yellow-suited Nagel. Essays in the accompanying Roland catalogue/magazine contain plenty of typical cringe-inducing combinations of forensic over-explanation and missing the point; Childish’s own writings and poems, and a short story by Walser are much more powerful. In the upstairs galleries, a wall of album covers featuring Pop Rivets, Headcoats (and Headcoatees) and Buff Medways, is a reminder of Childish’s prolific output in all creative fields. Poems as black vinyl words on the white cube cement the feeling that poetry can certainly be read in an art gallery, but preferably not on the walls.

A week or so later, Childish reads his poetry and shows some recent Chatham Super-8 films in the ICA Cinema. I’m prepared to be disappointed, and have a little bet with myself that he’ll sing The Bitter Cup (“whiskey runs through me like a sorrowful river”). Of course he does, but it’s also quite good, not least because he keeps up a self-deprecating anecdotal monologue (he offered to oil-wrestle portly Guardian art pontificator Jonathan Jones, apparently) between poems, and takes the piss a little out of the audience (who don’t look like a typical Childish audience, but what does a typical Childish audience look like?). Some of his intense hatred for family hypocrisy seems to have mellowed since he’s become a dad himself, and the patriotic stuff escapes me (a 20-minute movie about the re-enactment of a first world war march through France is the evening’s one bum note) but he’s hardly yet ready for treasure status. In both verse and person he remains committed to a open, egalitarian vision of human creativity, a harsh critic of art education and any kind of detachment from influence.

The talk by Stewart Home and Iain Sinclair is unconnected to the Childish exhibition, purloining its title from a forthcoming Verso book of urban essays, Restless Cities. Two such massive egotists on stage without a disciplinary interlocutor is always a risk: Sinclair begins by claiming that he may have invented Home as a character, or at least some of his ‘psychogeographical’ writings. Home puts him right on a couple of points about the London Psychogeographical Association and the Neoist Alliance (attempts to recuperate Italian left-wing communism through the establishment of one-man splinter groups) before launching into a series of anecdotes about the gangster antics of distant relatives. Home speaks in the same monotone he uses for his fiction readings, with an added air of weary resignation implying that he could tell you how everything really is, if only it was worth it. He’s oddly compelling: you think you’ll get bored of listening to him long before you do.

Sinclair reads a little from Hackney: That Rose-Red Empire. He’s at his most convincing in his opposition to the Olympics and the clear-cutting of East London. I’ve come across several people recently slating Sinclair for his adolescent pseudo-romantic solipsism and self-indulgent prose, but his consistent digs at the Olympics, as previously at the Dome, are an honourable sally. Sensitive to accusations of being a pair of ageing men only interested in the past, Home responds by mentioning his enthusiastic use of the internet (I can vouch that he posts a lot of videos on facebook), and the vastly improved quality of contemporary café food. Sinclair by contrast regrets the contemporary immanence of media: journeys of discovery are his bread and butter.

The subject of the ICA’s current crisis itself comes up: is it at risk of becoming a lost venue, like the Scala? Home mentions the notorious 1989 Situationist International exhibition at the ICA that historicised the SI (a trajectory aimed squarely at the gift shop) at the same time as it was coming into focus for the generation of avant-garde leftists that gave birth to the LPA. The first visit Home himself made to the ICA was to see an exhibition of Marvel comics in the bar. He mentions JJ Charlesworth’s analysis of the current crisis in Mute, and mounts a surprising (but half-hearted) defence of current director Ekow Eshun, arguing that the precarity and corporate orientation of the ICA goes back to Philip Dodd, and Mick Flood before him.

They seem in danger of historicising themselves. Sinclair offers that what matters to him, the work that he produces, is the connections offered by anecdote and coincidence. Old men trading on past glories? Here’s where the web tightens and pulls me in. The first time I visited the ICA was for the SI exhibition Home mentioned (people were handing out leaflets outside: who demonstrates outside an art gallery?). Childish is indirectly responsible for my early persistence in publishing my own poetry, via a friend, whose own chapbook, Jack the Biscuit is Skinhead, was inspired by Childish’s Hangman Press. I remember the friend who typeset Childish’s first novel, for another publisher, complaining about what a pig the job was (too fond of Celine, too particular about his ellipses). I used to send Stewart Home stamps in exchange for copies of Re:Action (one of which featured a headline quotation from one of my father’s books), my own (failed) mail art project used a box at British Monomarks, the same mail-forwarding company Home used. My connections to Home and Childish are precisely Sinclair’s tangential, anecdotal, coincidental connections. Not enough to build anything but a meandering thousand words or so out of.

Nevertheless, in the final days of Thatcherism, in the last decade before the internet exploded, Home and Childish offered evidence of a meaningful samizdat popular culture. Self-published chapbooks, small press book fairs, Xerox art workshops, the AK press catalogue and postal exchanges were all part of a real alternative to the depressing monotony of mainstream literature and music. It’s halfway to archaeology now, but it’s become a personal archaeology. That’s why the records are still in the collection, that’s why the books are still on the shelves.

<!–[if !mso]> <! st1\:*{behavior:url(#ieooui) } –>

It’s best not to have literary or artistic heroes. Leaders will always betray you, and heroes will always let you down. As they slide into their dotage, as their work becomes weak and repetitive, someone will always taunt you with their latest fatuity, reminding you how much you once loved them (in my case a role usually played by my father). Their books and records on your shelves, their pictures on your walls, are like mementos of an ex you can’t bring yourself to chuck away. So, best not to have the heroes in the first place. Except: some people’s work grabs you, and you can’t let it go. In the mid-nineties, three people who fell into this category for me were Stewart Home, Billy Childish and Iain Sinclair. Not only for how or what what they wrote, but also because they wrote about an interweaving, overlapping knot of things that mattered to me: poetry, resurgent Londophilia, anti-art polemics, post-Trotskyist politics, popular culture and the Situationist International.

Both Childish and Home have a history of polemic against my old employer, the Institute of Contemporary Arts (worse than either heroes or leaders, places like that: if you make the mistake of forming an attachment they’ll rip your fucking heart out). Home imagines its violent destruction by the masses in Defiant Pose; Childish as recently as last year targeted the place as part of Art Hate Week. And now, in the space of two weeks, all three of them appear at the ICA, just when it’s going through one of its episodic convulsions (mass redundancies and a departed head of exhibitions; the chair of its council is said to be flinging papers across desks in fury and falling through chairs at meetings). It’s like… well, it’s like something out of an Iain Sinclair book. A storm of synchronicity. This can’t be missed.

At the Childish’s private view it’s good to see old colleagues and catch up on current horrors. The new Childish paintings are better than the ones I saw at L-13 a couple of years ago. Estuarine landscapes and defunct steamboats, portraits of Robert Walser’s snowy corpse, a character that Billy integrates his own self-image into, via Knut Hamsun’s yellow-suited Nagel. Essays in the accompanying Roland catalogue/magazine contain plenty of typical cringe-inducing combinations of forensic over-explanation and missing the point; Childish’s own writings and poems, and a short story by Walser are much more powerful. In the upstairs galleries, a wall of album covers featuring Pop Rivets, Headcoats (and Headcoatees) and Buff Medways, is a reminder of Childish’s prolific output in all creative fields. Poems as black vinyl words on the white cube cement the feeling that poetry can certainly be read in an art gallery, but preferably not on the walls.

A week or so later, Childish reads his poetry and shows some recent Chatham Super-8 films in the ICA Cinema. I’m prepared to be disappointed, and have a little bet with myself that he’ll sing The Bitter Cup (“whiskey runs through me like a sorrowful river”). Of course he does, but it’s also quite good, not least because he keeps up a self-deprecating anecdotal monologue (he offered to oil-wrestle portly Guardian art pontificator Jonathan Jones, apparently) between poems, and takes the piss a little out of the audience (who don’t look like a typical Childish audience, but what does a typical Childish audience look like?). Some of his intense hatred for family hypocrisy seems to have mellowed since he’s become a dad himself, and the patriotic stuff escapes me (a 20-minute movie about the re-enactment of a first world war march through France is the evening’s one bum note) but he’s hardly yet ready for treasure status. In both verse and person he remains committed to a open, egalitarian vision of human creativity, a harsh critic of art education and any kind of detachment from influence.

The talk by Stewart Home and Iain Sinclair is unconnected to the Childish exhibition, purloining its title from a forthcoming Verso book of urban essays, Restless Cities. Two such massive egotists on stage without a disciplinary interlocutor is always a risk: Sinclair begins by claiming that he may have invented Home as a character, or at least some of his ‘psychogeographical’ writings. Home puts him right on a couple of points about the London Psychogeographical Association and the Neoist Alliance (attempts to recuperate Italian left-wing communism through the establishment of one-man splinter groups) before launching into a series of anecdotes about the gangster antics of distant relatives. Home speaks in the same monotone he uses for his fiction readings, with an added air of weary resignation implying that he could tell you how everything really is, if only it was worth it. He’s oddly compelling: you think you’ll get bored of listening to him long before you do.

Sinclair reads a little from Hackney: That Rose-Red Empire. He’s at his most convincing in his opposition to the Olympics and the clear-cutting of East London. I’ve come across several people recently slating Sinclair for his adolescent pseudo-romantic solipsism and self-indulgent prose, but his consistent digs at the Olympics, as previously at the Dome, are an honourable sally. Sensitive to accusations of being a pair of ageing men only interested in the past, Home responds by mentioning his enthusiastic use of the internet (I can vouch that he posts a lot of videos on facebook), and the vastly improved quality of contemporary café food. Sinclair by contrast regrets the contemporary immanence of media: journeys of discovery are his bread and butter.

The subject of the ICA’s current crisis itself comes up: is it at risk of becoming a lost venue, like the Scala? Home mentions the notorious 1989 Situationist International exhibition at the ICA that historicised the SI (a trajectory aimed squarely at the gift shop) at the same time as it was coming into focus for the generation of avant-garde leftists that gave birth to the LPA. The first visit Home himself made to the ICA was to see an exhibition of Marvel comics in the bar. He mentions JJ Charlesworth’s analysis of the current crisis in Mute, and mounts a surprising (but half-hearted) defence of current director Ekow Eshun, arguing that the precarity and corporate orientation of the ICA goes back to Philip Dodd, and Mick Flood before him.

They seem in danger of historicising themselves. Sinclair offers that what matters to him, the work that he produces, is the connections offered by anecdote and coincidence. Old men trading on past glories? Here’s where the web tightens and pulls me in. The first time I visited the ICA was for the SI exhibition Home mentioned (people were handing out leaflets outside: who demonstrates outside an art gallery?). Childish is indirectly responsible for my early persistence in publishing my own poetry, via a friend, whose own chapbook, Jack the Biscuit is Skinhead, was inspired by Childish’s Hangman Press. I remember the friend who typeset Childish’s first novel, for another publisher, complaining about what a pig the job was (too fond of Celine, too particular about his ellipses). I used to send Stewart Home stamps in exchange for copies of Re:Action (one of which featured a headline quotation from one of my father’s books), my own (failed) mail art project used a box at British Monomarks, the same mail-forwarding company Home used. My connections to Home and Childish are precisely Sinclair’s tangential, anecdotal, coincidental connections. Not enough to build anything but a meandering thousand words or so out of.

Nevertheless, in the final days of Thatcherism, in the last decade before the internet, Home and Childish offered evidence of a meaningful samizdat popular culture. Self-published chapbooks, small press book fairs, Xerox art workshops, the AK press catalogue and postal exchanges were all part of a real alternative to the depressing monotony of mainstream literature and music. It’s halfway to archaeology now, but it’s a personal archaeology. That’s why the records are still in the collection, that’s why the books are still on the shelves.